Common knowledge seems simple—it’s when everyone knows something, right? Well, not quite. It’s not just about you knowing something; it’s about everyone else knowing it and knowing that everyone else knows it, too.

A classic example is the Romanian Revolution in 1989. For years, everyone knew Ceaușescu was a tyrant and simmered in discontent. It wasn’t until a simple act during one of his speeches—a live-broadcast whistle snowballing into overwhelming condemnation—that a revolution began. The key wasn’t just that people were unhappy. It was that everyone saw everyone else was too. Within 24 hours, he was on the run, later executed.

X (formerly Twitter) should, in theory, be ideal for building common knowledge. Already, the platform is a digital public square, where anyone (almost anywhere) can say anything. Yet, common knowledge like “Ceaușescu is a tyrant” where everyone knows that everyone knows, rarely takes off. Instead, we get polarization. Every opinion that starts gaining traction ends up becoming a battleground, split along tribal lines—or “scissored.” Even X isn’t spared, as the platform risks turning into a flashpoint for debates about values (like free speech) and tools (like end-to-end encryption) that should transcend partisanship. This is neither a recipe for common-knowledge nor collective action, but for nonsensical conflict.

Can we avoid the “scissor of the crowd” and find the “wisdom of the crowd?” How can X become a common knowledge machine?

Community Notes is a good starting point. The open-source, verifiable tool allows users to add context or factual corrections to posts. Notes only get published if they get a high enough “helpfulness” score, especially by people who usually disagree.1 The intuition is that if different perspectives agree on a correction, it’s probably closer to the “truth” than if only supported by one side of the political spectrum.

But the problem is timing. Community Notes only show up ex-post, after a post has already gone viral and polarization has set in. Many have moved on and miss the correction.

If Community Notes is ex-post, is there a way to shift this process ex-ante, before a Post goes viral?

Introducing: Community Posts

Imagine a new mechanism—“Community Posts”—that combats polarization by surfacing common ground first. The idea is to stress-test a Post across different groups of followers who don’t necessarily talk, listen, or even agree with one another—what I call “polarity subsets”—to gauge whether it resonates before it’s widely shared. Here’s how it could work:

Step 1: Polarity Subsets. All followers have differences in behavior as measured by their likes, reposts, and social graphs (who they follow and who follows them). As the Post proposer, you pick a subset of uncorrelated followers—balanced for reach, with a minimum diversification threshold set by X. For example, you can handpick key anchors (such as experts or thought leaders), while X can offer different combinations to fill the remaining subset. Polarity subsets aren’t an echo chamber, but a subset of your followers balanced across different perspectives.

Step 2: ZK-Post: Send the post to your polarity subset, with a zero-knowledge (ZK) proof, confirming that the recipient follows you without revealing your identity. ZK proofs preserve privacy between users, though they still require trust in the platform. (See the Appendix’s discussion of architectural decentralization as a corrective.)

Step 3: ZK-Reposts. Recipients can either agree and pass the post forward to a polarity subset of their followers, or disagree and send ZK-feedback to you. These rounds repeat, forming a tree of polarity subsets through the social graph that pushes the post forward to new audiences, allowing you to gauge cross-tribal appeal through repost rates and feedback. ZK-reposts don’t show up publicly on any poster’s feeds, but instead appear in follower feeds with a proof: “zk-posted by n people you follow” or “n of the people you follow boosted this post.” To preserve anonymity, zk-posts should be staggered, with some initial recipients in the first subset getting the post later, mixed with subsequent re-posts.

Step 4: Going Public. Once the post gains enough traction and support across polarity subsets—having passed the social “stress test”—the post can go public, merging into open, public feeds. Anyone who has zk-posted to a polarity subset can now officially repost from their account, making the “Community Post” visible to all their followers for comments, reposts, or additional context. The reposting is staggered to ensure supporters reveal themselves gradually, without exposing other identities.

Step 5: Bridging with Notes. After a post goes public, people who disagree can add corrections or context with Community Notes. By this point, the post has already gained cross-tribal consensus, so Notes focus attention to bridging “low-hanging fruit” divides.

How are Posts different from Notes? Posts tap into the social graph and leverage participants’ observed behaviors (likes, reposts, and social connections) without new steps. By contrast, Notes gather additional feedback (“helpfulness” scores) through a side-channel to assess the Note’s value before publication. These mechanisms can interact in many ways, and what’s presented is a simple proof-of-concept. (For adaptations, see the Appendix.)

Why would this work?

The magic is Community Posts flip incentives. Instead of stoking division for attention, participants are rewarded for surfacing common ground—and that’s what you need for common knowledge.

Consider how common knowledge unfolds in meatspace. First, we start with self-knowledge (“I believe Ceaușescu is a tyrant”). As communication spears outward, self-knowledge turns into mutual knowledge, where different social groups start to realize that other groups share the same belief. Translation of context is key. Each group needs to be bridged on different facts and circumstances—or relevant context—so they can align on their interpretations and be motivated to continue spreading information to reach distant tribes. This process can take a while in meat-space, and as in Ceaușescu’s Romania, it might generate partial actions and partial rebellions along the way, which get snuffed out. But once enough different social groups share context and interpret facts similarly (finding common ground) common knowledge can culminate quickly— often preceded by a public act—when suddenly everyone knows what everyone knows, recursively.

Yet, this process of building common knowledge rarely happens on X. Instead, as a post starts gaining traction, instead of bridging tribes, it gets “scissored”—split into polarizing factions—before it can gain common ground. Soon enough, it’s forgotten, replaced by the next “current thing” or…animal memes.

Here’s why:

Context Collapse: Posts have context: the background facts, beliefs, and circumstances from which it originates. For the statement “Ceaușescu is a tyrant” to get off the ground in Romania requires some local knowledge of Romania—not the outrage of Berkeley communists divorced from context.

Capturing Attention: Attention-hackers exploit this vulnerability, stripping out subtleties in context to court conflict and win greater influence—turning posts into “rage-bait.” Rather than bridge across the social graph, baiters cut narrowly within and then widen divisions. Bots and humans acting like bots then amplify the divisions—often weaponized by adversaries to fill context gaps with disinformation. This drives engagement but produces contested knowledge, not common knowledge—confusion, not clarity.

Controversy & Cancellation: Once the cut is deep enough—often when baiters have made bedfellows with bots—a first-mover cancellation problem emerges, where anyone who voices a counter-perspective risks being harassed by toxic swarms that feed on cycles of outrage and condemnation. Interventions by high-status accounts—with a safety net of followers—can turn the tide, but these interventions also hand attention-hacks the visibility they want, while further centralizing status; the high-status intervener risks becoming the next target of the algorithmic scissor, entering the cycle of controversy.

Posts are either “lost in translation” or misinterpreted entirely. The process of sense-making breaks down, leading to fights, fatigue, and flight…or an exit to memes.

Community Posts aim to reverse every step of this spiral into polarization. Here’s how:

Correlation Discounts: In polarity subsets, followers with similar behavior are grouped as the same entity. This prevents bots or like-minded influencers from artificially boosting a post by spamming it. Instead, their feedback is discounted and treated “as one” when surfacing cross-tribal consensus.

Defensive Diversification: A Post that resonates with multiple, diverse clusters is harder to cancel. As more groups find common ground, they’re more likely to defend the post. This raises the “cost” of polarization because the more diverse the support, the harder it is to divide. “Security with diversity” defuses the first mover cancellation problem.

Bridging & Context Enrichment: A Post needs to resonate across diverse clusters to become common knowledge. Polarity subsets accelerate this process by rapidly testing a Post’s appeal across different tribes—and progressively expanding reach across new contexts, with feedback along the way. Community Notes step in once a Post has “gone public,” filling in any missing context and correcting inaccuracies. In short, Posts direct attention to finding common ground, while Notes bridge remaining divides.

To draw a corporate analogy, Community Posts act like a “poison pill” against polarization. If X is an attention auction, inflaming out-of-context divisions makes hostile takeovers of human attention too cheap. Whereas a corporate poison pill discounts the influence of a “hostile buyer” by diluting their shares, Community Posts discount the influence of accounts acting the same way by treating them as the same “hostile buyer” of attention. Just as a poison pill raises the cost of a takeover, similarly Community Posts also makes it expensive—socially and cognitively—to hijack human attention and polarize a post that’s already gained cross-tribal support.

Put another way: if the divisions that drive fame and fortune in X’s attention auction are weaponized to destabilize with chaos, Community Posts flips the script—leveraging the same divisions to re-stabilize on common ground.

What about Posts that never “go public?”

Not every post will go public, and that’s fine. A post stalling out is a useful signal—it shows where the divides are and how the post needs to be tweaked. By pushing posts through polarity subsets, the platform encourages reflection over reaction. Rather than scissor with simplicity, Community Posts rewilds with complexity.

Stalling out is also important in forming self-knowledge, as it is in forming common knowledge. Take the “Muddy Children Problem;” each child has mud on their forehead but can only see the mud on others, but not themselves. An adult enters and observes that at least one child has mud on their foreheads. Eventually, through logical inference and repeated observations by the adult (equal to the number of muddy kids), all the kids realize they have mud and step forward simultaneously. What’s often overlooked in this thought experiment is that self-knowledge (“I have mud on my face”) emerges simultaneously with common knowledge (“Everyone knows that everyone knows they have mud on their faces”).

But in real life, there is no independent oracle to observe “mud,” or declare who is right or wrong. Instead, humans are stuck with other humans judging them. Community Posts open a feedback loop, offering partial insights into how opinions resonate across different tribes. As Posts move through polarity subsets, feedback mirrors back beliefs and biases. In this way, Community Posts help us not only see the “mud” on others, but also become more aware of the mud on ourselves. By coming to know others—and their divisions—we also come to better know ourselves—and our own contradictions.

As posts pass through polarity subsets, something else happens: new coalitions form. When people discover unexpected common ground in a post, new alliances form along lines that didn’t exist before. Stress-testing a post triggers a feedback loop of mutual adaptation that reverberates across the network. As different groups engage, a process of “reflective equilibrium” ripples outward, where judgments get tested, refined, and re-justified—not just relative to principles and facts but also their coherence within a larger network of beliefs. Surprising overlaps and fresh points of disagreement get uncovered, opening new pathways for reconciliation. As this process of adjustment and realignment plays out, coalitions and networks criss-cross into greater complexity. If common knowledge emerges, it’s unlikely at an intersection you would have predicted.

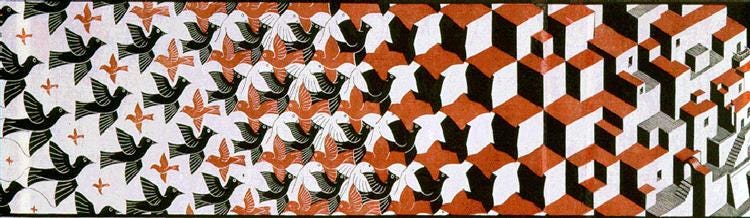

“Metamorphosis II” by M. C. Escher

What about Posts that “go public?”

A Community Post gains traction and eventually becoming common knowledge. So what? Just because everyone believes that everyone else believes “Ceaușescu is a tyrant,” does that make it actually true? Toxic swarms drive polarization, but common knowledge also has swarm-like origins. So how do we tell the difference between “good” and “bad” swarms? How do we know we are praising the saints, condemning the sinners, and eschewing scapegoats?

One approach is to think of Community Posts as an adaptation of Rawls’ “original position” thought experiment, with a computational turn. Instead of straining to strip away all the biases of our circumstance to arrive at a fair, impartial perspective, Community Posts does the opposite; leveraging the biases of our current positions—diversified against each other. Polarity subsets group uncorrelated followers, with the goal of wringing out idiosyncratic biases—really, risks in judgment. The idea is that consensus across these subsets may signal something more systemic and universal, agreed upon by multiple perspectives—something closer to a moral truth, like knowing “Ceaușescu is a tyrant.”

So about those muddy kids? The polarities should wash the mud off well enough, like water.

Thanks to Leo Glisic, Alex Tabarrok, Vitalik Buterin, Jay Baxter, Paula Berman, Kate Sills, Matt Prewitt, and Julian Sanchez for their thoughtful conversations, comments and criticism.

APPENDIX

Improvements

Credentials: Verifiable credentials (e.g., employment, educational background, professional certifications, geography) help differentiate between humans and bots while adding rich context for creating polarity subsets. Specifically, credentials expands the data relevant for diversifying subsets beyond merely ex post behavior (followers, followings, likes, resposts) to include ex ante commitments (who you work for, what oaths you have taken, etc.) Both ex ante and ex post information are useful in averting Simpson’s Paradoxes when clustering to surface genuine cross-tribal consensus. Credentials also can represent “nested networks,” which enable targeted bridging between smaller groups within a larger group.

Credential-gated Community Channels. Community channels are perhaps the most powerful step towards creating common knowledge. Not all communication is meant for a public square. These partially-private spaces nested within X’s larger public square recapture context, allowing groups to more freely deliberate, address disagreements, collaborate, and provide feedback—reducing out-of-context misinterpretation. These channels both avoid compression while adding depth to ZK-computation. Communities can run both internal and external Community Posts; find and form cooperative alliances with like-minded communities; and also join Polarity Subsets as a group. Bespoke bridges between groups can fine-tune disagreements and form greater networks for cooperation. (In a public square, Community Notes are a one-size-fits-all bridge.) Community channels also open a pathway toward decentralized content moderation, striking a third way between state and platform content moderation, pushing enforcement and governance down to communities.

Architectural Decentralization: ZK proofs protect the original poster’s identity, but relying on centralized servers risks backwards-inference by those with server access, potentially exposing ZK-posters before they have a chance to decide whether they want to “go public.” To mitigate this risk, no single actor should have totalistic access to an account feed (seeing all the posts you see). An architecture of decentralization implies federation and embedding users within their social networks (“communication channels”), using diverse and uncorrelated associations for security and recovery (like polarity subsets). By distributing risks and responsibilities across diversified association sets, privacy and accountability can work together, with “enforcement” requiring consensus and cooperation among diverse groups to share information, rather than unilateral control and surveillance.

“ZK-Posted by n very different people you follow” offers a useful metric for measuring how cross-tribal a post is as it spreads. ZK-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge) could ensure this calculation is verifiable without exposing sensitive details of the clusters or participants. Specifically, participants could compute and publish vectors of their followees, with clustering algorithms grouping these users based on behavioral patterns. ZK-SNARKs could then compute how many distinct clusters have engaged with the post and how many users per cluster have reposted it, producing a “cross-tribal score” that summarizes engagement across diverse groups.

Research Questions

Posts-to-Notes or Notes-to-Posts? I sketch a simple proof-of-concept based off X’s current implementation of Notes. But Posts and Notes could interact and complement one another in different ways. For example, while I say “Posts surface common ground, and Notes bridge remaining divides,” in another implementation, the opposite could be true; Notes could surface common ground posts, while passing a Note through polarity subsides could shake out remaining divides. The two mechanisms could also be combined; a Post could move through polarity subsets within a social graph with “helpfulness scores” along the way. Or, when a Post stalls in a subset, Notes could come into play, adding corrections and context to bridge those gaps. Experiments will strike the right balance.

Adaptation: Fork & Merge. It’s unlikely a Post hits the right framing on the first go. Participants should be able to improve on the Post by making “pull requests” to tweak wording and add context. With the original poster’s permission or consensus across subsets (another threshold), these requests can be “merged,” supplanting the original. At the same time, not every audience requires the same framing. Allowing participants to fork their own versions with tailored context for specific groups is also desirable.

Expertise. Facts and values may have a messy intersection, but to the extent we can build consensus on top of facts, we should. By extension, some people have more expertise on a subject matter, and should be given more weight in a subset (or take priority in a subset’s inclusion). Giving discretion to Post originators to choose some participants in their subset, and diversify the rest of the set against them is a simple way to anchor to expertise. But not everyone knows the experts, or knows what they don’t know. Are there measures of expertise, so for example, flat-earthers aren’t included in the set, or worse anchored to? Credentials are one measure (though many will disagree on their weight). Predictive ability is another. But increasingly predictive ability is hard to measure when participants can influence the very outcomes they predict, by virtue of their followings and position in a network. This is an open topic of research, and returns to the messy intersection of facts, values, and influence—a philosophical as much as an economic and computational problem.

Each Note is rated as “helpful, somewhat helpful, not helpful.” Instead of averaging these scores, the Notes algorithm weighs more heavily scores from participants who typically disagree on other notes. The key factor is “polarity values”—measuring the polarity of the user and the post—which are emergently discovered and can end up reflecting the political spectrum (really, dimensions) on any issue. Notes are published only if they attain a sufficiently high score (rated helpful by participants with opposite polarities), thus surfacing corrections with cross-tribal agreement. For more nuance, see Vitalik Buterin’s deep dive.